References

- Gee, G., et al., Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Wellbeing, in Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice P. Dudgeon, H. Milroy, and R. Walker, Editors. 2014, Commonwealth Government of Australia. p. 55-58.

- Wright, P., et al., Arts practice and disconnected youth in Australia: Impact and domains of change. Arts Health, 2013. 5(3): p. 190-203.

- Wright, R., et al., Community-based Arts Program for Youth in Low-Income Communities: A Multi-Method Evaluation. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 2006. 23: p. 635-652.

- Hamilton, M. and G. Redmond, Conceptualisation of social and emotional wellbeing for children and young people, and policy implications. 2010: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth.

- Bungay, H. and T. Vella-Burrows, The effects of participating in creative activities on the health and well-being of children and young people: a rapid review of the literature. Perspect Public Health, 2013. 133(1): p. 44-52.

- Cooper, P. and C. Cefai, Contemporary values and social context: Implications for the emotional wellbeing of children. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 2009. 14.

- The Kids Research Institute Australia. Core Story for Early Childhood Development and Learning. 2021; Available from: https://www.telethonkids.org.au/projects/HPER/core-story/.

- Kemp, M., Promoting the health and wellbeing of young Black men using community-based drama. Health Education, 2006. 106: p. 186-200.

- Wood, L., et al., "To the beat of a different drum": Improving the social and mental wellbeing of at-risk young people through drumming. Journal of public mental health, 2013. 12: p. 70-79.

- Bradt, J., M. Shim, and S.W. Goodill, Dance/movement therapy for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015. 1(1): p. Cd007103.

- Chlan, L., Effectiveness of a music therapy intervention on relaxation and anxiety for patients receiving ventilatory assistance. Heart Lung, 1998. 27(3): p. 169-76.

- Star, K.L. and J.A. Cox, The Use of Phototherapy in Couples and Family Counseling. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 2008. 3(4): p. 373-382.

- Staricoff, R., Arts in Health: A Review of the Medical Literature. Arts Council England, Research Report, 2006. 36.

- Parr, H., Arts and social capital. Ment Health Today, 2006: p. 23-5.

- Kagan, C., et al., Community Psychology Meets Participatory Arts: Well-being and creativity, in HOMINIS, International Conference. 2005, Research Institute for Health and Social Change: Havana, Cuba.

- Greaves, C.J. and L. Farbus, Effects of creative and social activity on the health and well-being of socially isolated older people: outcomes from a multi-method observational study. J R Soc Promot Health, 2006. 126(3): p. 134-42.

- Parkinson, C., Invest to save: Arts in health - Reflections on a 3-year period of research and development in the North West of England. . Australasian Journal of Arts and Health, 2009. 1: p. 40-60.

- Orpinas, P., Social Competence. 2010.

- Berk, L., Child development. 2015: Pearson Higher Education AU.

- Saarni, C., Emotional competence: a developmental perspective. 2000.

- CASEL. What is the CASEL SEL framework? 2020; Available from: https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/.

- Goleman, D. and P. Senge, The Triple Focus: A New Approach to Education. 2014: More Than Sound.

- Macnaughton, J., M. White, and R. Stacy, Researching the benefits of arts in health. Health Education, 2005. 105(5): p. 332-339.

- Ansdell, G., Musicology: Misunderstood guest at the music therapy feast? In: (eds.) . The 5th European Music Therapy Congress in Music Therapy in Europe. The 5th European Music Therapy Congress, D. Aldridge, et al., Editors. 2001: Napoli. p. 1-33.

- Chilton, G., Art Therapy and Flow: A Review of the Literature and Applications. Art Therapy, 2013. 30: p. 64-70.

- Beerse, M.E., et al., Biobehavioral utility of mindfulness-based art therapy: Neurobiological underpinnings and mental health impacts. Exp Biol Med (Maywood), 2020. 245(2): p. 122-130.

- Krout, R.E., Music listening to facilitate relaxation and promote wellness: Integrated aspects of our neurophysiological responses to music. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 2007. 34(2): p. 134-141.

- Wilson, E.O., Sociobiology The New Synthesis, Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Edition. 2000: Harvard University Press.

- Carlozzi, A.F., et al., Empathy as Related to Creativity, Dogmatism, and Expressiveness. The Journal of Psychology, 1995. 129(4): p. 365-373.

- Sinding, C., R. Warren, and C. Paton, Social work and the arts: Images at the intersection. Qualitative Social Work, 2012. 13(2): p. 187-202.

- De Botton, A. and J. Armstrong, Art as therapy. 2013: Phaidon Press.

- Magsamen, S., Your Brain on Art: The Case for Neuroaesthetics. Cerebrum, 2019. 2019.

- Greene, M., Variations on a blue guitar: The Lincoln Center Institute lectures on aesthetic education. 2001: Teachers College Press.

- Gulla, A., Aesthetic Inquiry: Teaching Under the Influence of Maxine Greene. The High School Journal, 2018. 101: p. 108-115.

- Keating, C., Evaluating Community Arts and Community Wellbeing: An Evaluation Guide for Community Arts Practitioners, P.b.E.C.f.A.V.D.C.C.C.o.W.a. VicHealth, Editor. 2002, Effective Change Pty Ltd.

- Tomyn, A. and R. Cummins, The Subjective Wellbeing of High-School Students: Validating the Personal Wellbeing Index—School Children. Social Indicators Research, 2011. 101.

- Stewart-Brown, S. and K. Janmohamed, Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale. User guide. Version, 2008. 1(10.1037).

- Greco, L.A., R.A. Baer, and G.T. Smith, Assessing mindfulness in children and adolescents: development and validation of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM). Psychol Assess, 2011. 23(3): p. 606-14.

- Gilbert, P., et al., The development of compassionate engagement and action scales for self and others. Journal of Compassionate Health Care, 2017. 4(1): p. 4.

- Smith, B., et al., The Brief Resilience Scale: Assessing the Ability to Bounce Back. International journal of behavioral medicine, 2008. 15: p. 194-200.

Supports

This section investigates the concept of mental health – what it is and what it isn’t. It also provides some strategies for educators to deal with mental health issues that may occur in the arts room.

In this section we will consider the total construct of mental health. As presented in the SEW-Arts website SEWB can be viewed as a component of mental health and forms an important part of mental health promotion.

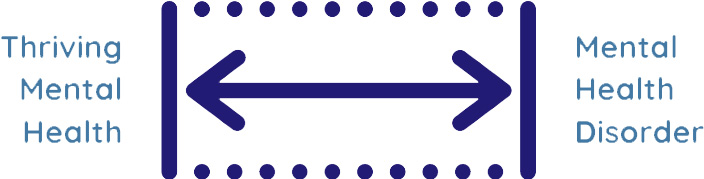

Definitions suggest mental health as a dimensional construct. Mental health does not seem to be all or nothing (i.e., you either have mental health or you don’t). Rather, mental health is better viewed as a continuum. In this way, mental health could be viewed as:

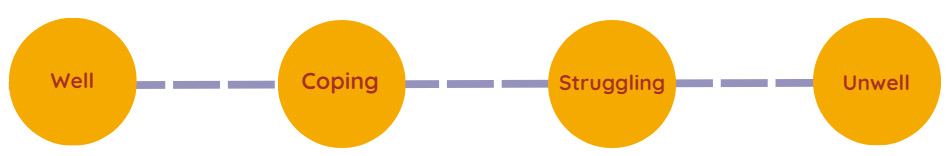

The Australian Government’s National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy suggests a similar continuum:

Such a continuum recognises that there are time points along the entire length of dimension for intervention opportunities to promote well-being and improve mental health outcomes. The principles of preventative and early intervention, both evidence-based pillars of mental health, are reflected in this approach. This resource aims to support opportunities for mental health promotion through a focus on developing SEWB.

What is not mental health?

It is important to be specific in conceptualising mental health, and it can be helpful to identify concepts that are part of the current well-being lexicon but are not ‘mental health’. These concepts might indeed impact on an individual’s mental health but are not fundamentally what we understand an individual’s mental health to be.

A young person’s capacity for resilience when coping with stressors matures alongside their own developmental trajectory. It is important to take a developmental perspective on how we are interpreting a young person’s behaviour, thoughts and emotionality.

Young people, and indeed all of us, are constantly adjusting to stressors. For example, we adjust to the stress of extreme temperature, access to natural light, hunger, sleep deprivation, changes to routine… the list goes on and that is before we consider social-emotional factors such as identity, relationships and assessment/evaluation pressure.

It is important that we remember that it is expected and often developmentally appropriate for young people to grapple with adjusting to stressors. It is normal that such grappling might bring with it a degree of psychological distress and changes to functioning, such as: regression or surge in gestures of independence; urges to avoid, quit or withdraw; intense or unexpected expression of emotions including (but not limited to!) sadness, anger and poor tolerance for frustration; and changes to behaviour that someone might “not seem like their usual self”.

Mental health experts are specially trained to recognise individual differences in the threshold between normative adjustment distress and mental health difficulties.

Disability

Definitions of disability vary, due to such factors as policy and legal jurisdiction. For example, the WHO conceptualise disability as resulting “from the interaction between individuals with a health condition, with personal and environmental factors including negative attitudes, inaccessible transportation and public buildings, and limited social support”.

In this way, the Social Model of Disability can also help with clarifying disability as a concept.

Neurodivergence

Refers to “variations between human minds occurring naturally within a population, and includes conditions such as autism, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyspraxia, dyslexia and dyscalculia” [32].

Taken together with definitions of mental health and disability, we can see that there might be an intersection with such concepts as neurodivergence. However, we can also understand that neurodivergence and disability are not mental health conditions, and are in fact separate constructs.

Mental health & young people in Australia

Links for more information about understanding mental health and young people in Australia:

- Young Minds Matter Survey (The Kids Research Institute Australia)

- Commonwealth Govt’s Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

- National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy

Some recommended expert and peak organisations for specialised youth mental health support and education in Australia:

- Headspace(information for young people and also adults, including parents and adults)

- Beyond Blue

- Butterfly Foundation

- Kids Helpline

Support for Teaching Artists

Fit your own oxygen mask first

The most helpful thing an adult can do, when they are aiming to support the wellbeing of others, is to cultivate their own self-care.

Coping when tricky stuff happens in the arts class

Young person displays highly distressed or dysregulated behaviour

It is encouraged that organisations have a clear policy that supports their teaching artists should a young person display inappropriate and/or unsafe behaviour during class. This could be an individualised organisational response or the ALGEE mental health first aid response.

Consider the immediate safety of the group and the individual and recruit in additional support if required (i.e., call for organisational help). De-escalation principles are a helpful first response.

Communicate appropriately with organisation administrators and young person’s caregivers (don’t keep it a secret that something has happened).

Be prepared by completing Mental Health First Aid and De-escalation training

Be aware of any already existing behavioural management or support plans that your students might have. Some students might have existing plans that are integrated with school, at home or other contexts.

You suspect bullying

It is encouraged that organisations have a clear policy that supports their teaching artists should a young person disclose bullying or if the educator has reasonable suspicion that a child is being bullied. Bullying is different to ‘one-off’ acts of aggressive behaviour and is a repeated act by an individual or group that target a person who finds it hard to stop it from happening. Bullying can be verbal, physical or social or happen online (cyberbullying).

Children often do not seek out support but struggle to deal with bullying situations by themselves. If they do ask for help it’s important to Listen, Acknowledge that bullying is wrong, Talk about options and End with encouragement (the LATE strategy).

It is important to also let their parents know about the bullying with the child/young person’s permission to maintain trust, unless you feel they are at risk of harm.

For support on strategies to address bullying in your classroom or advice to give young people go to:

- friendlyschools.com.au

- https://bullyingnoway.gov.au/

- https://kidshelpline.com.au/teens/issues/bullying

You suspect abuse

It is encouraged that organisations have a clear policy that supports their teaching artists should a young person disclose abuse or if the educator has reasonable suspicion that a child is at risk.

Outside of that, helpful WA links to help familiarise yourself with recognising abuse and neglect, and responding to a child disclosing abuse are:

- https://www.wa.gov.au/organisation/department-of-communities/concerns-the-safety-or-wellbeing-of-child-or-young-person

- https://www.wa.gov.au/organisation/department-of-communities/child-protection

- https://www.wa.gov.au/service/community-services/community-support/mandatory-reporting-of-child-sexual-abuse-wa#:~:text=Anyone%20who%20is%20concerned%20that,.wa.gov.au